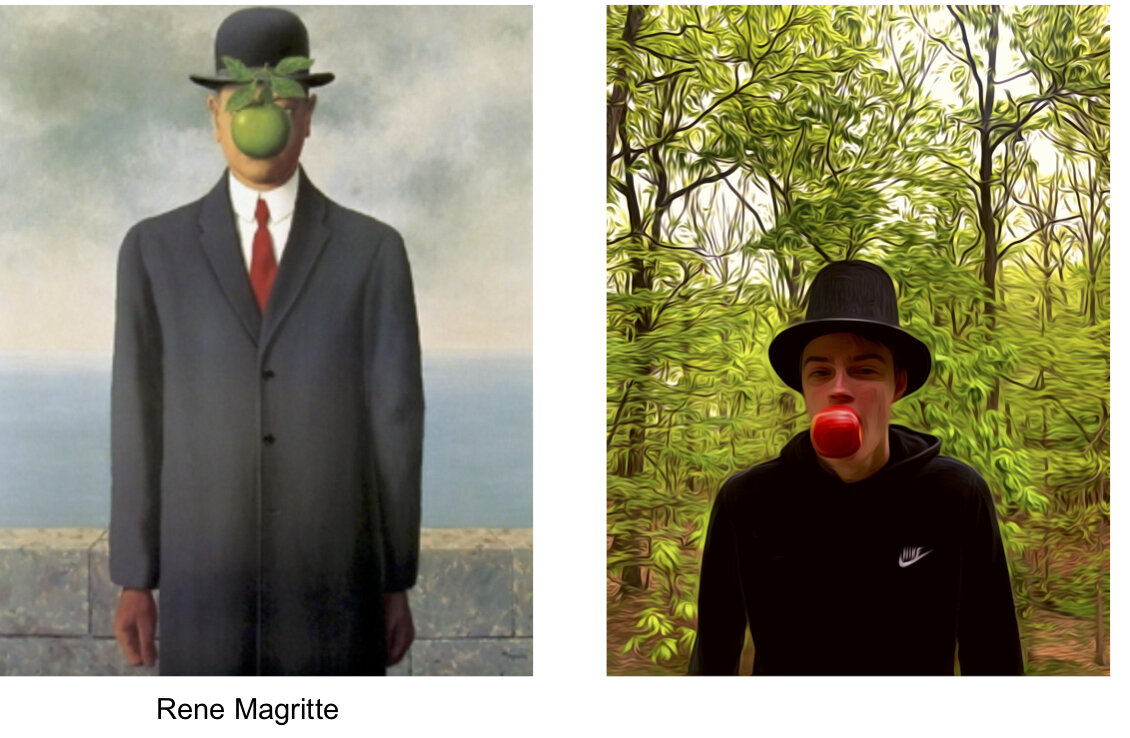

I love telling my students about Ad Reinhardt’s all-black painting, titled Abstract Painting,1963. They inevitably give me the same bemused look that I must have given my high school teacher back in 1970 when she showed it to us. Oddly enough my students are still surprised, to this day, by the thought that such a painting even exists. Despite all the incredible, and sometimes shocking, works of art we have become accustomed to seeing in the past half century, my students--along with many adults I know— still recoil at the notion of an all-black painting.

As a result of this very predictable reaction, I have come to call this painting (and others like it), I could have done that! paintings.

Does that phrase sound familiar to you?

The Ad Reinhardt Conundrum

As with so many works of art, some of which you may think are complete bunk, the truth is that, over the decades, Ad Reinhardt’s all-black paintings have slowly revealed themselves, to be modern masterpieces. I hope this post can shed some light on why that is. I hope that if you are one of those who thinks they are complete bunk you will at least consider giving these paintings a second chance.

Reinhardt’s “Ultimate” series of black paintings were created near the end of his life. This might seem quite logical to some of us who feel closer to the end of our lives than the beginning. Not out of some dark, morose vision of our own mortality, but out of intellectual economy, as we contemplate What it is that we really need? What is really necessary?

Searching for life’s essential ingredients is a gradual process of elimination. Through an endless stream of questions, artists and scientists spend much of their lives searching for order in the universe. Eventually, once they have become comfortable with the chaos (!), they might take a bold leap of faith —and that is where true discoveries begin.

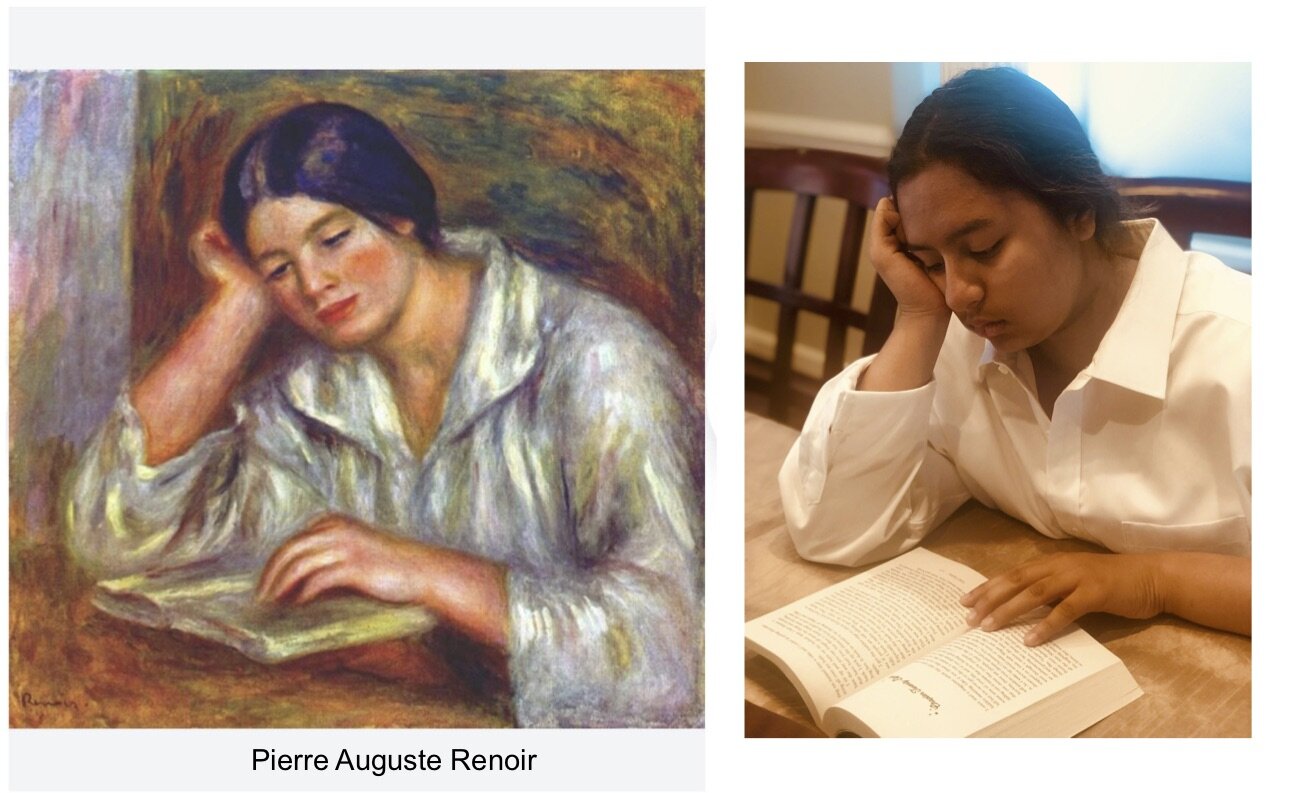

Change is never easy, and nowhere is this more evident than in the art world. In France during the nineteenth century the Impressionists, a small group of mostly landscape painters, began to chip away at the classical standards for artists that were dictated by the all-powerful Academy. The Academy was steeped in centuries of tradition defined by richly detailed paintings and classical themes. The Impressionists rejected the standards of academic painting and began stripping away the details, broadening their brush strokes, and eliminating the “story lines.” These artists wanted to concentrate on the essential ingredients of nature, relying on the power of color, texture, and light to express the more ephemeral sides of our existence, the inexplicable parts of human feeling that otherwise get lost in the small grinding details of classical painting. This is where the story of abstraction begins, between the brush strokes and swaths of paint first laid down by J. M. Turner, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, and the Impressionists.

In 1968, before cell phones and personal computers, when the “fame obsessed” pop artist Andy Warhol said, “In the future everybody will be world famous for 15 minutes,” someone hearing that for the first time might have thought he was trying to be cute, or that he was pretentious, or crazy—but these days, with even our cats and dogs going viral within minutes of posting pictures of them on social media it is not at all impossible to think that Andy Warhol was, somehow, way ahead of his time! He probably would not describe his breakthrough works of art or social commentary as “taking leaps of faith”--he was much too ironic for that--but call it what you will. He trusted his instincts, and those instincts took the art world, and the world at large, to places it had never been before.

For the moment, let’s suspend all the reasons why you might “reason,” or speculate why Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract, 1963 is an important painting or not an important painting. Even if you have never seen it, certainly you can imagine what it looks like! So just suspend judgment for a moment, about things you may have read about why this painting was as shocking back then as it is considered important today, and let me tell you how I came to understand it. (After all this is my blog, and it is my hope that my aha moment might help some “serious doubters” come to appreciate not only this painting, but understand many other contemporary works of art as well.

First of all, just because something is in a museum doesn’t mean that you have to like it! You are definitely not alone. Some things are difficult to understand even for regular museum goers and art lovers. However, with just the tiniest amount of curiosity you might find yourself wondering why something is in a museum. After all, museums, metaphorically speaking, draw an imaginary line around the most important things we value as a culture, in fact, they draw a line around many one of a kind things. And Ad Reinhardt’s all-black painting is certainly one of a kind! You probably won’t get any street cred if you or anyone else tries to imitate his Ultimate series.

Reinhardt’s painting had to happen. If he had not done it maybe you, or I, or someone else might have been called on to do it —-and we could be famous too! But with the evolution of modern art, beginning well before the turn of the twentieth century, one common denominator, one abstraction after another, it makes perfect sense that eventually there was going to be an all-black canvas, and it was Ad Reinhardt who was called upon by his muse to accomplish the task. Still using oil paint on canvas, still using traditional materials, at a certain point the only thing left to do was literally nothing. Zero.

Getting Down to Ones and Zeros

An all black-painting, or nothing? It is interesting to note here, that the digital* code running your computer and cell phones operates on a series of 1’s and zeros. The first electronic computer using this digital code was not invented until 1973, more than ten years after Ad Reinhardt’s painting of the first all black series began. I say this because art and architecture and science and technology have followed each other like the strands of DNA winding around each other since the beginning of time; and if you think Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are great (they were 7 years old at the time of Reinhardt’s painting), and if you think that their work changed the world, then you should consider giving some credit to Ad Reinhardt too; because he helped pave the way, at least conceptually, if not artistically, to where we all are today.

The Heart of the Matter

I did not know it at the time, but the seeds that were sown for my understanding and acceptance of this painting came many years after I first learned about it in high school.

By 1981 a decade had passed since I had graduated from high school. I had finished art school on the East Coast, lived briefly on the West Coast, and eventually got the travel bug and made my way to Europe. An unplanned few months turned into a few years there, living an unconventional lifestyle. I studied even more art in Paris, lived in a gypsy caravan by the side of the Marne River, and sold pots and pans in the street markets of Paris (see SDF or click here) and eventually moved to New York City. That is where, at last, for the first time in my life I would encounter the real--and by then, at least in my mind--“infamous” all-black painting by Ad Reinhardt in the Museum of Modern Art.

I didn’t go to the museum that day to see that painting in particular, and in fact I didn’t even know it was there. I didn’t know the name of it, and really, about the only thing I knew was that an all-black painting existed somewhere in the world. As I moved from gallery to gallery, eventually I entered a well-lit room flooded with natural light and there it was, Ad Reinhardt’s work right before my eyes! It was an all-black painting on an all-white wall. I think I was alone at the time, and the only person standing in the gallery. The painting was much larger than I had imagined it to be, and I was stunned by its presence. I have stood before many works of art and felt unmoved but this was different.

It was a moment when my passion for making art, my travels, and my love of life all came together. The light came on. Not for historical, or philosophical, or formal aesthetic reasons, but for very personal ones. I was instantly transported to a scene from my everyday “gypsy” life on the banks of the Marne, outside of Paris.

The Source

The word for a well in French is source. And there was a well on the property where the gypsy caravan I had acquired was parked. This source was a natural spring bubbling up from underground to the surface, surrounded by a small ancient stone shelter. The outside was completely overgrown by vines, making it look more like the entrance to a cave than anything else. It had a fairytale quality about it, and for that reason I had snapped a picture of it way back when.

The Source

There was no door to the entrance of the spring, only a small stone path that led the way to its mysterious and slightly ominous darkened opening. On a warm day you could feel the cold, moist air emanating from the well, pulling you nearer until your field of vision turned black as you reached inside to fetch a pail of water. I often felt like I was being pulled in by a mythical spirit, as others must have felt in centuries before.

This is why I was so stunned by Ad Reinhardt’s all-black painting. I was drawn into it like a well. Like the source. Which is practically the definition of abstraction.

The most important thing that I have to say here is this: to truly understand any work of art you need to bring something of yourself to it, and try not to let your experience be colored by other people’s definitions. To appreciate art, patience is required. It is something we have run out of in this day and age of instant gratification. It took me ten years, and traveling halfway around the world before I could fully appreciate this painting.

Some artworks are easy to dismiss at first glance, but I am of the mind that most artists are not trying to pull the wool over your eyes. I think it should also be said that most paintings are not made to entertain you. They can be entertaining, but they were not made for the purpose of entertaining you. They are the result of someone’s honest searching for the answers to some of life’s most compelling questions. They are the result of an artist’s intellectual adventure and you, as the viewer, are gifted with the possibility of joining them on that journey—or the possibility of finding a completely unintended meaning, an even richer one that is completed by your own life’s experience.

Here is the kicker...

Many years later--as an art teacher, and a person who enjoys finding connections and intersections between things, and sharing my insights with my students--it occurred to me that there was one more thing I could convey to my students about why the “I could have done that” all-black paintings are so important.

People of all ages, worldwide, are enormously attracted to minimalist modern architecture. The relationship is easy to understand, and it cements my case for the importance of Reinhardt's all-black painting. Because without Reinhardt’s leap of faith, and others like him who took similar leaps** many of the contemporary spaces that we love to occupy today, from flat pack houses to museums, to monuments and memorials, might not have happened without these visionary artists leading the way.

Viet Nam War Memorial, Washington D.C.

There is much, much more written about Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting, 1963 than I can say here but I think it’s important to briefly mention something about his technique and his personal philosophy. He didn't just take a big paint roller loaded with flat black acrylic house paint and roll it on the canvas! You can read about the painstaking care of how he built up colors and textures to arrive at his final grande oeuvre in many articles and textbooks. Words like vibrance, depth, and transcendence, come to my mind, but the rest is up for you to discover.

I hope you will find your own source and the next time you’re in a museum, remember to bring yourself to the paintings. Don’t expect the paintings to come to you.

Student: “I could have done that!”

Teacher: “Then why didn’t you?”

Anyway, I hope I have been able to give at least a few doubters of that all-black painting, Abstract, 1963, by Ad Reinhardt, something new to think about.

Stephen Rueckert

*Before digital, here is a sculpture of mine made from a mechanical/analog adding machine otherwise known as a cash register! Check out my lost work of art called, St. Industry, circa 1982.

** Ad Reinhardt, Jackson Pollock, Joseph Albers, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Piet Mondrian. Architects, Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. Musician, John Cage, to name only a few.