In the morning of the day the pandemic of 2020 closed down our school for the remainder of the year, Caroline, my star ceramic artist, a senior at Middleburg Academy, was perfecting her hand-spun creations on the potter’s wheel, trimming her pots and preparing more clay for her next class. Students in my three-dimensional design class had already begun cutting their 4’ x 4’ sheets of half-inch birch plywood; they were building a full-size chair, from scratch, no nails/no glue, and of course, using their own designs. The students in my figure drawing class, standing at their easels, were just discovering the subtleties of light and shadow, after learning how to “see” the simple shapes and how to draw a layout. Then came the news. All the students were told to go home. This was no snow day. This was a closing without a clear end in sight. This was Covid 19.

Fortunately for us, our school had embarked upon a S.T.E.A.M curriculum several years earlier. At that time, I was hired to help incorporate the “Art” element into the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. Our school had already migrated over to a Google platform before the pandemic shutdown, and within a week, we would be able to make a flawless transition to online teaching.

Hit the “Easy” button? Not exactly...

Over that weekend I wracked my brain, trying to figure out how to teach ceramics online. Remote learning and sculpture? Teach three-dimensional design to kids suddenly isolated at home, with no art supplies, tools, or materials? Virtual clay? Yeah, right! Some of the kids had work spaces, some did not..How was I supposed to do this?

“I know,” I thought, “I will get a Bob Ross wig! That will certainly be entertaining.”...Well, yes, for about thirty seconds... and with three months to go, ummm...

To be honest, I was terrified.

I knew that I had to really rethink--hard--what my role as an art teacher meant in the whole scheme of things. After more than 20 years of pre-pandemic teaching I thought I had a pretty good idea about what I was doing, but teaching art online was going to be a whole new ballgame.

I am no stranger to shocking transitions. I began my upper school teaching career at Saint Albans School in September of 2001. I had moved my then young family down to Washington D.C. from Brooklyn, New York, where my studio was located in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, looking across the river to lower Manhattan and the World Trade Center.

Not two weeks into my first really important teaching job, our country was suddenly under a terrorist attack. From the National Cathedral, where St. Albans is located, smoke could be seen rising from the Pentagon. The World Trade Center fell in NYC, Flight 93 crashed to the ground in Pennsylvania, and as we all know, the unbelievable had happened.

For quite some time afterward, there were no numbers: the stock market stopped, and very little commerce took place. Our nation grieved as the world turned to prayer, poetry, music, and art. I lost a friend that day as so many others did too; far worse for those who lost family members.

Our school gathered in the chapel to remember the lost souls on Flight 93, in New York City, in Washington D.C. Many members of our school community had personally been affected. Afterwards, I proposed to the head of school that we create some sort of memorial, and with his approval I got started on the project.

I created a work of art, a vessel if you will, to hold paper cards that were distributed throughout the school and the school community. People, young and old, and from all different parts of the Saint Albans community--students, parents, teachers, staff and alumni returned their cards to me, having drawn on them, written poetry, personal notes, reflections, collages, songs. After I received them, I placed them into the twin towers of my sculpture—a time capsule, in memorial. You can see it here.

Through these drawings, I learned how important it was for people to express themselves during times of loss. Especially children! There were so many voices, so many different pitches and tones. Some were solemn, some angry, but each expression in its own way, I believe, was also a form of healing.

Fast forward, back to Covid 19 and my art teacher/teaching dilemma.

Quarantined at home, suddenly cut off from their friends, their grandparents and other family members, some already facing personal loss, I had to quickly improvise. Convincing my students who were in isolation, mostly in their bedrooms and glued to their computers—that there could be no better time than now to get out and make art, was a hard sell to say the least. All of a sudden art just seemed like more work on top of everything else that they were expected to accomplish from their bedrooms, beginning at 8:10 in the morning and running until 2:45 in the afternoon. Distance learning is very different from a normal school day on campus. For my students, arriving at the art studios used to be a breath of fresh air in their day. Not anymore.

As if the school day hadn’t changed, teenagers were suddenly spending hours every day behind their screens, teleconferencing, learning math, science, English, history, Latin: it didn't seem possible to me that this could end well. The students were understandably resistant. The fact that art is often, subliminally or not, thought of as being at the bottom of the academic food chain —since it won’t be on the SAT— has always been a strike against it, and that made this situation even more challenging. Even in the best of schools, art is often seen as mere decoration, a vocational pursuit rather than an expansive gateway into virtually everything that life has to offer.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CREATIVITY (but still a part of this story)

On behalf of our college-bound young masters and future custodians of the world, my questions for the Gatekeepers of the College Admissions Process (in both high school and university) are the following: Where is there a college entrance exam that tests for creativity? That tests for a student’s resilience, and their ability to cross-pollinate ideas across the curriculum? Where is there a portfolio of creative accomplishments (in any media or any form) that might offer creative solutions to our many social, cultural, and global problems? Where is there a test that offers a glimpse into a student’s level of self knowledge—and his or her ability to demonstrate compassion, empathy for others, and a willingness to work together to find solutions to our problems?

Show me a poem, a dance, a work of art, or anything that can address these issues from an original perspective. Show me answers that don’t have to be right. Show me possibilities.

If these habits of mind don’t begin to be developed early; and if they cannot be observed (in any subject area, not just art) by the time a student is ‘ready’ for college, I maintain that we have not prepared our students well. Not for college, and certainly not for the world.

We have created Zombies. And remember, these are Zombies that will run the world, for better or worse.

Ahh, okay, I feel better now.. and now, back to my students.

Going online wasn’t the time for any of my high falutin’ ideas about art and healing, sustenance, tolerance, building compassion, and the important role that art plays in a well balanced education.

To quote from one of our family’s favorite movies, Field of Dreams, “If you build it they will come.” This has always been something of a mantra for me in teaching. If you provide the energy, enthusiasm, passion, and materials, people instinctively will be attracted. A little magic helps too.

However, teaching via Google chat under these conditions sterilized the whole process. Dragging teenagers out of their beds at eight o’clock in the morning and convincing them this was a great time to get inspired and get their hands dirty was not going to work. Turning it into another academic class like Art History would only add more academic pressure; also, let’s face it, learning about art history does not replace making art. I love it, but it is just not the same.

I hate cell phones in the classroom. They are not allowed in my class without permission. I once told a group of parents, while holding up my cell phone, “Your child has a thief in their pocket!” Kids today will never need to learn how to use a compass. They will be sucked into vacuous social media, games, and answers for things that they will never have to think about. It’s all there for them. They don’t have to think for themselves.

This is not entirely true of course, but here is the kicker: my students’ cell phones became a lifesaver for me in the first weeks of teaching online.

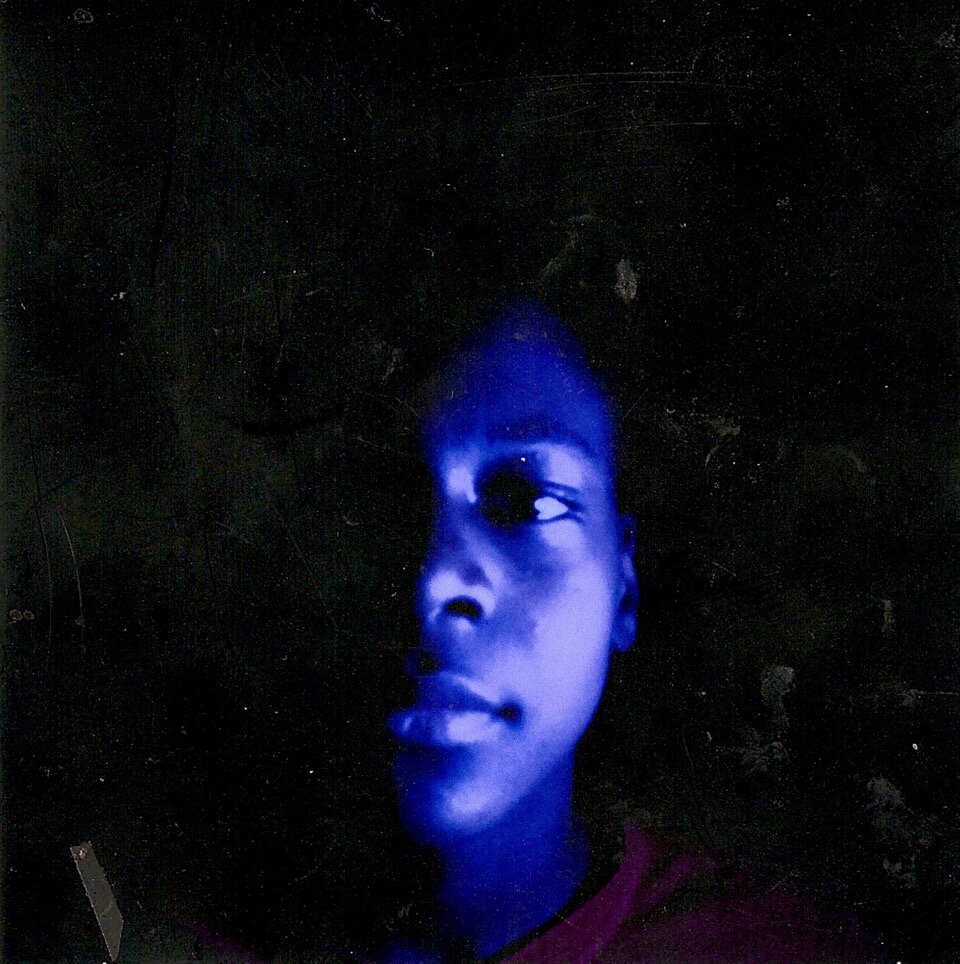

Every kid owns one, and one thing about cell phones is that in terms of expressiveness, immediacy, and resilience, they are a “medium” not unlike clay. Every cellphone has a camera. And you can feel the same kind of spontaneous, immediate joy when you snap a picture with your phone as you feel when you first push your thumbs into a hunk of malleable clay. To make an initial impression in both cases requires little thought. To make a pot, on the other hand, requires much more time and attention; and to get beyond snapping a random picture does too.

In the beginning my assignments were wide open, but after about a dozen photos of their pets, I thought it was about time to take a look at the works of some well known photographers, and some “how to” videos on YouTube. So I started guiding them a bit more. They also learned how to use their photo editing apps, and discovered new ones. From there, their camera angles changed, as did their level of confidence.

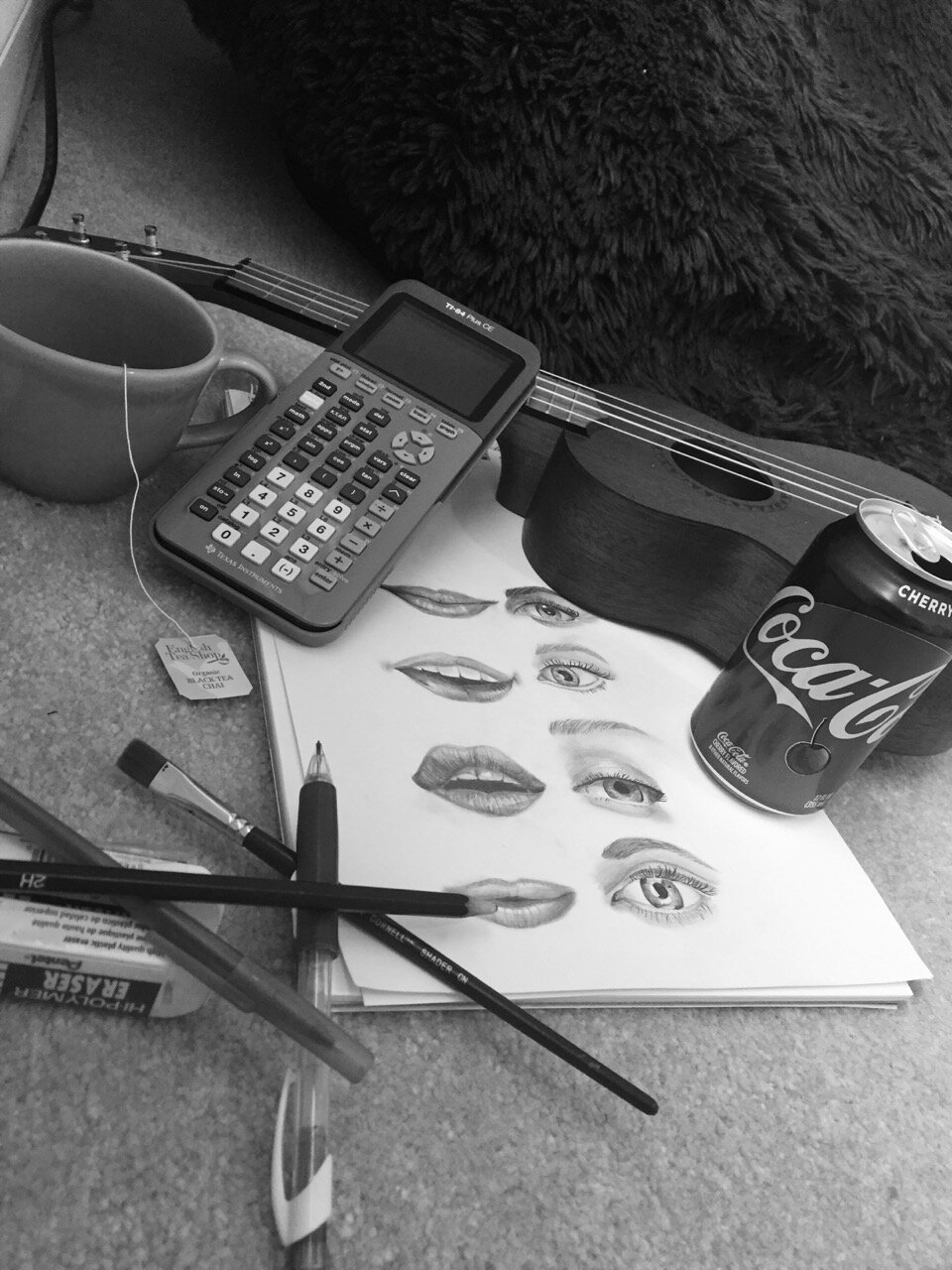

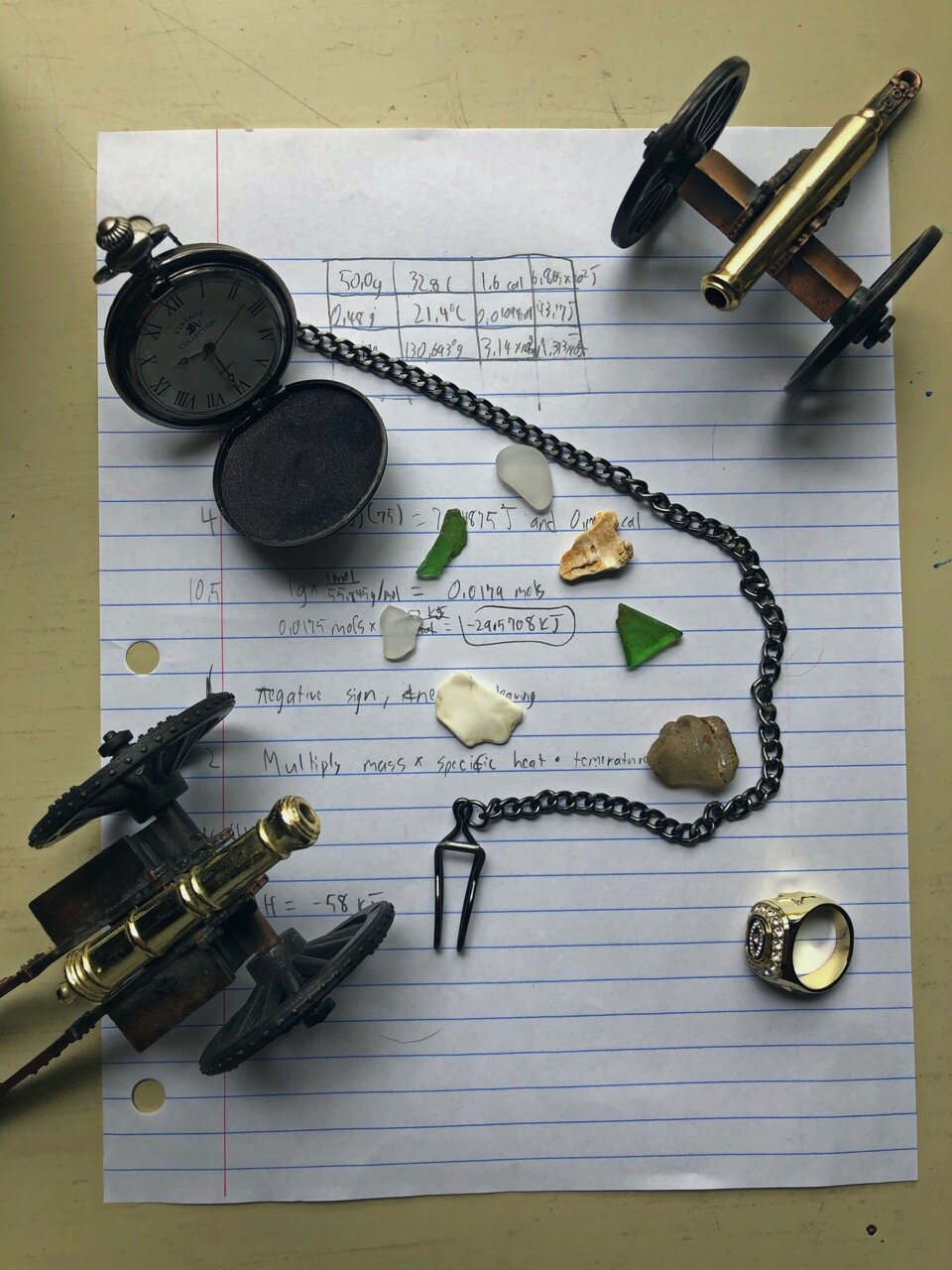

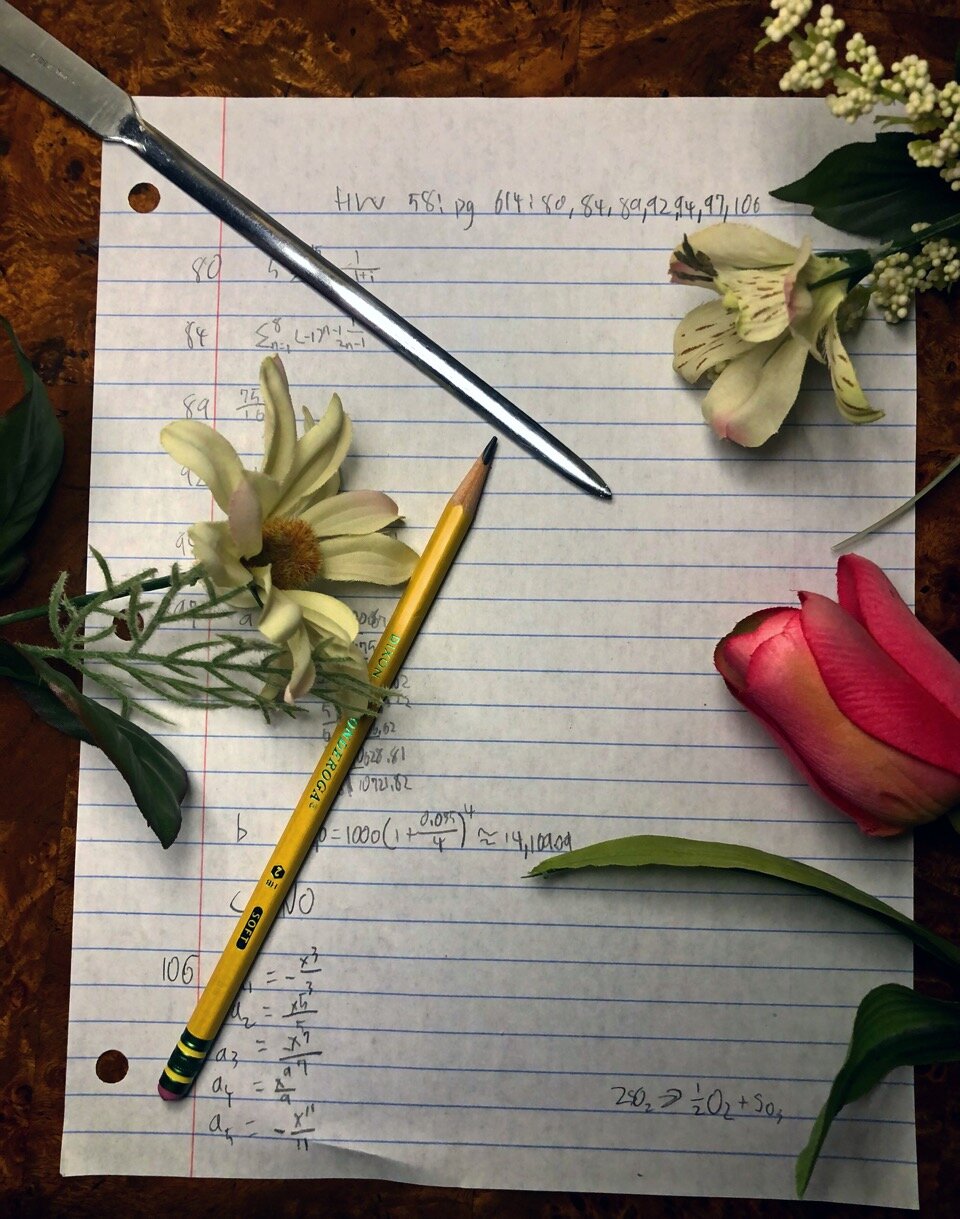

As the semester moved on, their photos matured both technically and conceptually, as each of them found ways to uniquely portray their experience of being quarantined. Their senses of humor emerged. So did their loneliness, their boredom, their anxieties, and then..long after.. an ephemeral sense of time and beauty and light and shadow—the stuff of art--began to emerge.

So, thank you, cell phones. I still don’t like you very much, but I must admit, you saved the day. Many of my students struck up a keen interest in photography during the lockdown. And it was more, much more, than just snapping pictures. They have taken some really interesting pictures, to document a time they will never forget.

As often as I could, I told the students to get off their computers and get outside. And I introduced them to earth artist, Andy Goldsworthy. Honestly, I didn’t care what they made. I just wanted them to go outside. And they did. One of my favorite students, who thinks art is “stupid,” created one of my favorite works by hanging all the tools in his garage on a string, an homage to Alexander Calder!

Their serendipitous responses to my online prompts turned out to be the most fun. No, we didn’t dig deep into the subject of art as we do in the classroom; and often the craftsmanship that I usually demand of them wasn’t there. But their responses to my prompts were by and large playful, joyful, and often soulful. This is alI I could ask for, as an art teacher “in times like these.” And I am thankful to each one of those students for being so brave, so patient, so willing to step up to the challenge we were presented with.

Teaching is an imperfect art. As much as I hated teaching online (a sentiment shared by my colleagues and students) it forced me to improvise. I had to come up with ways, on a moment's notice, to think beyond what I would do if we were in the classroom. It forced me to accept the need to compromise, to find the good in “less is more.” And it amplified the truth that in order for teaching to work, there must be trust between all parties, and everyone must do their part.

For those reasons alone, I believe that the history of teaching will forever be changed. And that what the pandemic gave us, among other things, was a chance to think of new ways to deepen and enrich our teaching, using new media.

Now: can I please get back to the classroom?

After Mark di Suvero, by the boy who thinks art is stupid. I have feeling he might be an artist one day!

A work by artist, Mark di Suvero